Remembering Teen Atomic Physicist and Spy Ted Hall and Aug. 19, 1949

And imagining what would likely have happened to the world had the US emerged from WWII with an unchallengeable nuclear monopoly

Americans, Japanese and Russians can be forgiven for not knowing that Aug. 29 is a vitally important anniversary date in the history of war. Like July 16, it slips right by us each year unnoticed, though though the two dates recall hugely significant events and have a lot in common.

On July 16, in 1945, The US detonated the first atomic bomb in history in a test blast in the Alamogordo Desert of New Mexico.

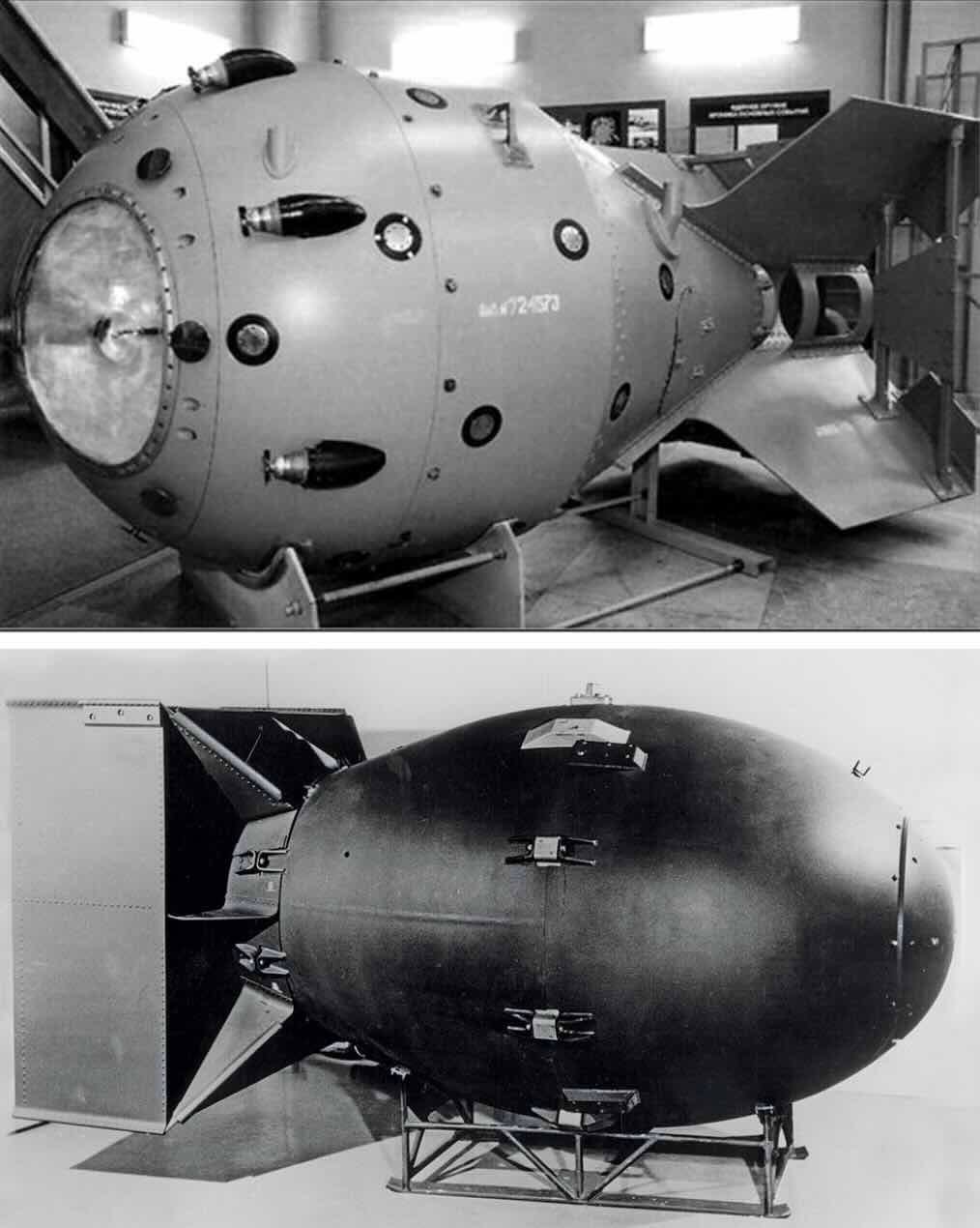

On August 29, just four years and few weeks later, the Soviet Union successfully detonated its own atomic bomb in a similar setting: Semipalatinsk, on the arid steppe region of Kazakh region of eastern Siberia.

Both tests were conducted in secret.

The first bomb, a complicated plutonium-based weapon equal to 25,000 tons of TNT, sent a towering mushroom cloud into the stratosphere over the New Mexico desert, launching the nuclear age. Its success had US military strategists and national security officials rubbing their hands excitedly as they anticipated the USbeing the sole post-war possessor of a weapon incomparably more powerful than any ever created. Because the Trinity Test had been conducted in secret with no public announcement, and wanting to demonstrate that power to the world, and specifically to the Japanese government, military and people (and to the Soviet Union), they pushed the scientists at Los Alamos to complete an operational plutonium bomb and a uranium bomb. They did this so they could demonstrate their ability to totally destroy two cities in Japan before the war was ended.

President Harry Truman and his national security team, after pointlessly murdering several hundred thousand civilian Japanese men, women and children, looked forward to a future in which the US would be the world’s unrivaled superpower. To ensure that future , even as WWII was still raging in the Pacific, they also set America’s nuclear scientists and engineers to work trying to industrialize the mass production of atomic bombs. The goal, as I explain and document in my just-published book Spy for No Country: The story of Ted Hall, the teenage atomic spy who may have saved the world (Prometheus Books, 2024), was to have 400 Nagasaki sized atomic bombs and the hundreds of B-29 bombers needed to carry them, ready by the early 1950s to carry out a “nation-killing” preemptive nuclear strike on the Soviet Union in order to prevent it from developing its own atomic bomb.

This, it must be noted, was the same Soviet Union that had been America’s main ally in the war against Nazi Germany, and which was even then making good on a promise to the US to join in the final assault against the Japanese military in Manchuria on on northern Japanese islands.

That monstrous plan, fortunately, was prevented thanks in significant part to the courageous efforts of a prescient teenage physicist at Los Alamos — 19-year-old Theodore Hall, who for almost two years worked at Los Alamos on developing the plutonium bomb, and then, beginning in mid October 1944 shared what he knew with the Soviet Union.

He actually succeeded in passing those detailed plans to a courier working for the Soviet NKVD (a precursor of the KGB), sometime between the bombing of Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, and the Japanese Emperor Hirohito’s Aug. 15 surrender radio broadcast to the Japanese people and to Japanese troops in the Asia-Pacific.

That ream of documents, arriving in Moscow by diplomatic pouch and passed on to Soviet nuclear scientists, gave the head of the Soviet bomb project Igor Kurchatov the confidence to tell Soviet leader Joseph Stalin that he should postpone efforts to develop a uranium bomb and focus all available resources on copying the American’s successful plutonium bomb, the fissionable core of which was far easier to obtain than the hard-to-isolate fissionable U-235 isotope of uranium, which exists only in trace amounts in naturally occurring uranium.

Ted Hall, whose work on the complex implosion system required to successfully detonate the plutonium bomb, was recognized as critical to its success by Los Alamos scientific director Robert Oppenheimer, was thus a key figure in the creation of the bomb that inaugurated the Nuclear age at Alamogordo, and the bomb used on Nagasaki — the last atomic bomb to be used in war for the last 79 years. Hall was also a key figure in the USSR’s acquisition of its own successful plutonium bomb, which was successfully tested on Aug. 29, 75 year ago. It was an event that led to cancellation (or at least indefinite suspension) of US plans to destroy the Soviet Union.

Ted Hall, when he was recruited by the Manhattan Project while a 18-year-old junior Harvard physics major at Harvard in November 1943, was told the secret weapon project he would be working on was to prevent Hitler from creating it first. But as it became clear to him and many more senior Project scientists during 1944 that Germany was losing the war and would never get an atomic bomb, he became increasingly worried about its continued development and how the US might use it in a post-war world.

Hall died of kidney cancer in 1999 at the age of 74, having never been charged or prosecuted as an atomic spy for reasons so incredible that I urge readers to get a copy of my book to discover it. His is a tale far stranger than any spy fiction author could get away with offering up. Researching and writing my book in the 2018-2023 period, I obviously had no opportunity to ask Hall how it felt to have helped the Soviets build the atomic bomb. That said, I am certain that his bold spying effort, by preventing a post-war US monopoly on the bomb, must have gone a long way towards allowing him to assuage the guilt he must have lived with for helping to create it.

Indeed, as horrible as was the mass murder by the US of almost a half million Japanese in Hiroshima and Nagasaki at a time that Japan’s military and its industrial infrastructure were entirely destroyed, those deaths and the Russian bomb test that made nuclear weapons un-useable because of the huge risk of retaliation, have given the world three-quarters of a century of nuclear peace.

It’s been, to be sure, an anxious 75 years, with some close calls, but so far the nuclear standoff has held.

I conclude my book with an account by Hugh Gusterson, a professor of anthropology and public policy at the University of British Columbia. Writing in the Aug. 16, 2023 issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists about his meeting in the mid-1990s with a nuclear weapons scientist who had worked on and witnessed the first Soviet atomic bomb test, he recalled:

“In what was admittedly an inartfully phrased question, I asked, ‘How did you feel when you realized you had given Stalin the bomb?’ He looked a me steadily under craggy eyebrows as the question was translated, then said evenly, ‘I felt at last I could sleep again after four years. Finally we were safe from the Americans.’”

I know Hall felt much the same sense of relief when he learned of the Soviets’ successful test of their own atom bomb, because his wife Joan Krakover Hall, whom he met and married in 1947, told me. She also recounts that incident in a documentary film I co-produced that was released in 2022 titled “A Compassionate Spy,” directed by Steve James. In that film she recounts his breaking into a smile as a news flash breaks into a radio broadcast they listening to over breakfast in the fall of 1949 reporting that the Soviets also have the atomi bomb. (Joan Hall passed away in June 2023 at the age of 93.)